History of Canadian Military Chaplaincy

There have been military chaplains in Canada since before there even was a Canada. The first Anglican Eucharist was celebrated in Canada aboard a ship in Baffin Bay, 03 September 1578, by the Reverend John Wolfall,  who was the chaplain to the third Frobisher expedition. Throughout the 17th century, the religious order of Recollect priests accompanied French explorers to Canada and served in the French garrison settlements. The Anglican presence in Canada began when regiments recruited in New England, assisted by a British naval squadron, captured the French stronghold ofPort Royal. The Reverend John Harrison, chaplain to the supporting British squadron, conducted the first Anglican Divine Service in the French Chapel at Port Royal, 10 October 1710.

who was the chaplain to the third Frobisher expedition. Throughout the 17th century, the religious order of Recollect priests accompanied French explorers to Canada and served in the French garrison settlements. The Anglican presence in Canada began when regiments recruited in New England, assisted by a British naval squadron, captured the French stronghold ofPort Royal. The Reverend John Harrison, chaplain to the supporting British squadron, conducted the first Anglican Divine Service in the French Chapel at Port Royal, 10 October 1710.

Over the years of our country’s early history, French and British chaplains, many of who remained in this country, played a significant role in bringing Christianity to Canada. The churches that were established in Canada continued to provide clergy to care spiritually for the members of the military forces stationed and serving here. Between 1796 and 1802 chaplains serving with the British military forces inCanadaall had to be members of the Church of England in order to be enrolled as full time garrison or brigade chaplains. In the absence of a military chaplain, local parochial clergy were brought in by commanding officers to offer the duties of the chaplain. The majority of chaplains serving in Canada during this period were actually parochial clergy, and although the majority were Anglican, following 1802 Roman Catholic and Protestant clergy were also able to be employed as chaplains.

THE WAR OF 1812

A distinguished group of clergy made themselves available to support our military forces at the outbreak of the War of 1812. Many in this group were Anglican clergy, including such notable individuals as the Reverend Richard Pollard, the Reverend Robert Addison, the Reverend George Stuart, and the Reverend John Strachan who went on to become the first Bishop of Toronto. These, and others like them, served well in their duties as chaplains; they gave comfort whenever they could, to the sick and wounded, and they also contributed significantly to the growth and culture of Upper Canada.

AFTER CONFEDERATION

Even if members of the clergy had readily accompanied and supported Canadian military personnel in the War of 1812, the Fenian Raids of 1866, and in the Northwest Rebellion of 1885, the federal government was reluctant to create an official military chaplaincy following Canadian confederation. As a result, from 1896 until the outbreak of the First World War, the government sponsored an honorary militia chaplaincy, authorizing one honorary chaplain for each unit, on the condition that no expense to the public was incurred. Even before many of these new militia chaplains took office, war rumors from South Africa stirred the nation.

THE BOER WAR

Although the government initially had intended that no chaplains would be sent with the Canadian contingent to South Africa, this decision proved unacceptable to the Canadian churches, who took steps to ensure that clergy from their respective denominations were identified and dispatched to provide religious and spiritual support.

In the end, six Canadian chaplains served on active duty in the Boer War, along with two Y.M.C.A. workers. The initial contingent of the Royal Canadian Regiment embarked with a Methodist chaplain: Reverend W.G. Lane; a Presbyterian chaplain: the Reverend Thomas Fullerton; and a Roman Catholic chaplain: the Reverend P.M. O’Leary; as well as an Anglican chaplain: the Reverend John Almond – who was hastily added, after the direct intervention by the Anglican Bishop of Quebec with the Prime Minister.

Two additional chaplains were embarked with a subsequent contingent of cavalry and filed artillery. These included Anglican chaplain, the Reverend J.W. Cox, and Roman Catholic chaplain, the Reverend J.C. Sinnett. The South African campaign confirmed that a chaplain’s influence was directly proportional to the amount of danger and hardship they shared with the troops, and the provision of chaplaincy became an important consideration within the Canadian military form this time forward.

WORLD WAR I (1914-1918) – ORGANIZATION

The Boer War was followed by almost a decade and a half of peacetime militia ministry. Then in 1914, when the Canadian Contingent was quickly assembled to go to France, hundreds of clergy followed their soldiers to the assembly point at Valcartier. At first, no chaplains were to go. Then the Minister of Militia, Sir Sam Hughes, initially chose just 33 chaplains — only six of whom were Roman Catholic — and he appointed an associate of his, the Reverend Richard Steacy, an Anglican priest from Ottawa, as the Director of the Canadian Chaplain Service.

Although the number of chaplains would increase significantly during the course of the war, the lack of sensitivity to the religious needs of Roman Catholics continued to be a concern, and would become a contributing factor to the formation of separate Protestant and Roman Catholic Chaplain services in 1939. It was only in 1917, after Colonel Steacy was replaced as Director by fellow Anglican, and Boer War veteran, Colonel John Almond, that inter-denominational tensions began to be resolved, and a Roman Catholic priest, the Reverend W.T. Workman, was appointed as Almond’s assistant Director.

During the First World War, 524 clergymen served in the Canadian Chaplain Service. Of this number 447 served overseas, and a number of those chaplains served with distinction, such as George Anderson Wells, an Anglican priest, who actually finished the war as the most decorated chaplain in the British Commonwealth. There were still other chaplains who paid the supreme sacrifice, such as Father Rosaire Crochetiere, the beloved chaplain of the Royal 22e Regiment, who was killed in an artillery barrage near Flanders, in France, on April 2nd 1918. Padre Crochetiere was described by the men of his regiment as being like “a father, a brother, a confidant, and a friend.”

At first, the chaplains were misunderstood. They were used to look after canteens and entertainment. Eventually these duties were handed over to auxiliary forces such as the YMCA and the chaplains moved forward into the trenches. Years of suffering and sorrow stripped away every personal disguise and every religious trapping. Denominational barriers faded as the chaplains called upon every spiritual resource they could muster to meet the challenges of suffering and death.

One such chaplain, upon whom many called, was Canon Frederick George Scott, who was padre of the 1st Division of the Canadian Corps. Described as one of the most beloved men in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, Canon Scott became a respected confidant, friend and spiritual guide to many junior and senior officers as well as enlisted men. When he returned from the war he continued to be revered by thousands, and in 1934 he published a memoir entitled The Great War as I Saw It, in which he describes his own search for the buried body if his son Captain Henry Hutton Scott who was killed in the 21 October 1916 attack on Regina Trench, near Courcelette.

AFTER THE FIRST WORLD WAR

After the First World War, the Director’s office in Ottawa closed down and the Canadian Chaplain Service dropped out of existence for a time. Civilian religious organizations lost interest in the military, although many ex-chaplains joined with units of the Non-permanent Active Militia. Many of them went to camp with their units in the summer and paraded with them when they had the opportunity. Most rendered good service as they were able, but few were able to render a complete service.Writing about the inter-war years, Anglican chaplain C.G. Hepburn reported “that it was a definite weakness that there was no Chaplaincy authority in Ottawa to control appointments in consultation with Church Authorities and to direct and coordinate the activities of these chaplains”.

WORLD WAR II (1939-1945)

In the chaotic months following September 1939, Canada’s military leaders fought franticly to rebuild a fighting force that had largely been disbanded after the First World War. The last thing on the military mind was the need for a chaplain service. Enter: Anglican Bishop George Anderson Wells, Bishop of the Diocese of Cariboo, and to this day the most decorated chaplain in the British Commonwealth. From his home in Victoria, through high-ranking Militia contacts, Wells offered to serve in any capacity that was needed. Within weeks he was on his way to Ottawa, with his First World War files in hand, in order to re-establish the chaplain service.

The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops was already organized. They could not tolerate serving under the same conditions as they had faced in the previous war. Months earlier, Defence Minister and Quebec city MP, “Chubby” Powers, had gone to the Roman Catholic authorities in Quebec to request the use of the large Quebec churches as possible air raid shelters, and in the negotiations Archbishop Roy had bargained for a separate chaplain service. A deal had been struck and to Wells’ surprise, Roman Catholic Bishop Charles Nelligan, of the Diocese of Pembroke, had been named to establish a parallel Roman Catholic chaplain service.

WORLD WAR II – ROLE

The first chaplains overseas were experienced men who had served in the First World War. It was not until D-Day that a steady stream of younger chaplains was provided for front line soldiers. Most of the activity in the Royal Canadian Air Force took place at home. There was a lot of flying training and a lot of crashes. Often it was the chaplain who took the bad news to next of kin and loved ones. Overseas, RCAF chaplains stayed close to the aircrew. In bomber command they would see the boys off and would wait for their return. There having been no Canadian naval chaplains prior to this war, those who served with the Royal Canadian Navy looked for ways to help. Someone decided that they could free officers for hard sea duty if they volunteered to censor mail. As the size of the navy grew this became an interesting but impossible task. Chaplains came to realize that the real place for them was with the men in action and, as the size of the ships increased, were able to go to sea.

Approximately 1400 Canadian chaplains served during World War II. By the end of the war, the senior chaplain of the third Division was able to report: “The fighting during October, as we concentrated on canals, dykes, etc. was marked by extreme difficulty in handling the wounded and the dead. To hear chaplains tell how they would “cat walk” across canals and dykes, stealthily crawl to where a lad was lying wounded, dress his wound, help to load him, then crawl all the way back, made one feel that every last padre should be awarded a medal”.

WORLD WAR II – PRISONERS OF WAR

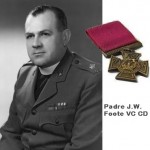

Canada’s most famous padre POW of the Second World War was the Presbyterian chaplain, Major (H) John Weir Foote, VC. Padre Foote served with the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry and was captured on the beach at Dieppe. Newspapers of the day called him Padre X of Dieppe. The men called him “an angel of mercy”. No one will ever know how many people Foote helped that day. The wounded he carried to the landing craft owed their lives to him. When given a last chance to escape, Padre Foote chose to remain on the beach, because that is where his services were most needed. Years later, when the Victoria Cross was awarded, he placed the medal in his regimental museum. He said that many of the men who fought that day deserved the award as much as he did.

Canada’s most famous padre POW of the Second World War was the Presbyterian chaplain, Major (H) John Weir Foote, VC. Padre Foote served with the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry and was captured on the beach at Dieppe. Newspapers of the day called him Padre X of Dieppe. The men called him “an angel of mercy”. No one will ever know how many people Foote helped that day. The wounded he carried to the landing craft owed their lives to him. When given a last chance to escape, Padre Foote chose to remain on the beach, because that is where his services were most needed. Years later, when the Victoria Cross was awarded, he placed the medal in his regimental museum. He said that many of the men who fought that day deserved the award as much as he did.

WORLD WAR II – PADRE WALTER BROWN

As padre to the 27th Armoured Regiment (Sherbrooke Fusiliers), Anglican chaplain Captain (H) Walter Brown, was one of the first Canadian chaplains to land at Juno Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944. He served his men and even buried some of his fellow soldiers at Beny-sur-Mer, now a Canadian war cemetery. Within days, he was reportedly captured by an SS unit and listed as prisoner of war, and then as missing in action. The truth, however, was far darker. Padre Brown was summarily executed by his captors — the only Allied chaplain killed in such fashion during the entire war. His body was found five weeks later by the side of the road, and was subsequently buried at Beny-sur-Mer on July 11. He rests there still, but his chaplain communion kit made its way home to Canada, and was eventually donated to the Huron College Chapel, in London ON, where it is used regularly for worship, and remains an abiding symbol for the college community of “the demands of sacrifice and the necessity of the willingness to serve.”

POST- WORLD WAR II

After the Second World War, on 9 August 1945, the Governor General in Council authorized the establishment of separate Protestant and Roman Catholic Chaplain Services, for the RCAF, the RCN and the Canadian Army. On 1 October 1945, the Adjutant General issued an order setting up these separate Protestant and Roman Catholic chaplain services, with an initial establishment of 137 Protestant chaplains and 162 Roman Catholic chaplains.

Many of the military personnel just back from the war, were understandably intent on getting on with their personal lives, and many of our military bases began to fill up with young spouses and children. Permanent married quarters needed to be built, followed by schools, stores, and even chapels. While on the one hand, military chaplains still had to be trained, prepared and equipped to participate in military operations, they were also now expected to minister to the military families and communities that became established on our Canadian Forces Bases and Stations across Canada and in Europe.

KOREA(1950-1953)

While the conflict in Korea (1950-1953) has been termed a ‘police action” it was very much a war with the total number of UN forces, including South Koreans, killed, wounded or missing being 996,937. There were over 25,000 Canadians serving in this campaign with 1,558 casualties including 516 dead with 312 deaths in combat. A lot of time was spent preparing the Canadian contingent for the deployment. This meant that the navy was on station long before Canadian soldiers were available to deploy. Messages were sent out from Ottawa to clergy who had been combatants in the Second World War. Only a few volunteered to go. One of these was United Church chaplain, Captain Ray Cunningham. He already held a commission from the previous war, but was the first chaplain who had permission to have substantive instead of honorary rank.

Due to long periods of static warfare, permanent camps were established behind the front, and there was a lot of patrolling. At first chaplains were assigned to units in such camps, but later chaplains would rotate to the front lines. As in previous conflicts, the most successful chaplains were the ones who were deployed closest to the troops. One such padre was Anglican chaplain Howard Johnson, who at the end of his tour of duty was awarded an MBE (Member of the British Empire). The citation related how he had “devoted himself wholeheartedly to the welfare of the men and units under his care, to the point of endangering his own health.” On many occasions he “visited forward positions” and “was always on hand to encourage the wounded and to minister to the dying, giving comfort and encouragement wherever his presence was required.”

PEACE SUPPORT OPERATIONS

As one of the architects of UN peacekeeping, Canada was one of the nations that provided a contingent when the United Nations Emergency Force was dispatched to Egypt in 1956 to be a buffer between Egyptian and Israeli forces. Canadian troops subsequently served in the Congo, in Egypt, in Cyprus and on the Golan Heights. In addition, Canadian military personnel have served on an International Peace Commission in Vietnam (1973) and an International Peace Force in the Sinai (1986).

The operational commitments of our Canadian Military have never really ceased for very long. Whether it was the Cold War or the first Gulf war; whether it was with NATO or the UN, or in response to some emergency situation here at home, or in some other part of the world, wherever our soldiers, sailors and air personal have been deployed, our chaplains have always been deployed with them, to such places as: the former Yugoslavia and Haiti, and to Rwanda and Afghanistan; or in response to such things as ice storms, flooding, or even civil unrest — right here at home — or to earthquakes, hurricanes or even tidal waves that have devastated some foreign land. Chaplains have been consistently present with troops provide pastoral care and spiritual support.

UNIFICATION OF THE CHAPLAIN SERVICES

A partial integration of the three chaplain services (land/sea/air) took place in 1958, and Chaplains General (RC) and (P), with the rank of Brigadier-General (or equivalent) were appointed. In 1967 the Reorganization Act of the Armed Forces became law. The three Army, Navy and Air Force chaplain services became the CF Chaplain Branch (P), and the CF Chaplain Branch (RC). With the arrival of integration, chaplains would not necessarily spend their entire career with one element, but instead were required to serve in sea, land, or air environments, as the exigencies of the service necessitated.

Reorganization of the chaplaincy continued. In 1994, the Canadian Forces Chaplain School and Centre (CFChSC) was officially opened at CFB Borden, in order to design and deliver professional occupation training for all CF chaplains (P) and (RC). This was a significant milestone in development of single fully integrated Chaplaincy (P&RC). In 1995, an administrative integration of the two Chaplain Branches (P & RC) was initiated, with a unified Chaplaincy HQ and a single Chaplain General (rotating initially between P & RC incumbents every 2 years.)

In 2002 the two divisions within the Branch – Roman Catholic and Protestant – began the process of amalgamating their two separate classifications, Chaplain (RC) and Chaplain (P), into a single military occupation. What had once been two parallel but distinct Roman Catholic and Protestant Chaplain Branches, has now merged into a single ecumenical and now multi-faith Chaplain Branch. New Branch insignia, motto and emblems were created, and Ode to Joy was approved as the new Branch March, replacing Onward Christian Soldiers.

On June 27, 2003, Imam Suleyman Demiray was enrolled as the first ever Muslim chaplain to serve within the Canadian Forces and on March 13, 2007, Rabbi Chaim Mendelsohn was enrolled as the first Jewish chaplain within the Canadian Forces since the Second World War.

CHAPLAINCY TODAY

While military chaplains and chaplaincies have long been a part of the military presence in Canada, there has been a considerable evolution in our Chaplain Branch as we have continued to strive to address and meet the spiritual needs of Canadian Forces personnel and their families, in ways which respect and reflect the religious diversity of this nation. Today, all of our military chaplains, regardless of what faith tradition they come from, are expected to be able to provide a comprehensive ministry, for all of the military personnel and families who entrusted to their care.

This unique approach to Chaplaincy within the Canadian Forces has led to the continuing development of a truly a multi-faith approach to ministry, which is focused on: “ministering to our own, facilitating the worship of others, and caring for all.” As a result of this, the Canadian Forces Chaplaincy is becoming recognized throughout the world for its ecumenical and interfaith approaches to ministry within a pluralistic military environment.

In June 2012, a new Primary Branch Badge was approved as a unified emblem representing the Chaplaincy as a whole. This new Primary Badge, which incorporates images of the Tree of Life and the Light of God, does not replace the faith-specific cap badges worn by the chaplains, but represents the unity of a multi-faith Chaplaincy, and reflects its common mission: to address to the deep spiritual needs of all Canadian Forces members and their families.

Further Resources:

History of Navy Chaplaincy – A Canadian Perspective