The following marks the fourth instalment of our report on Justice Camp 2016. Read parts one, two, and three.

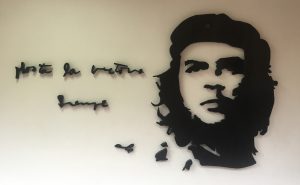

The resort town of Varadero leaves a different impression than most cities in Cuba. Dominated by hotels, shops, and restaurants, its raison d’être is catering to the tourists who contribute valuable income to the island nation’s economy. Among the myriad souvenirs on display, the heroic, determined face of Che Guevara stared out at us from every conceivable product.

It was in Varadero that the Anglican Video team and I planned to rendezvous with the Justice Camp social engagement immersion group on the evening of Wednesday, May 4. Having been unable to reach the group during the afternoon due to poor cell reception, we finally located them inside the Plaza America Centro de Convenciones y Comercial (Convention and Commerical Centre), where participants had congregated after an afternoon swim at the beach.

We moved outside to some stairs overlooking the beach and palm trees, the scenery beautiful even under rain and grey skies. Sipping from a can of Bucanero Fuerte beer, I took notes as we began a discussion about the economic, social and environmental impact of the tourism industry in Cuba.

Over the course of the dialogue between Canadian and Cuban participants, we learned much about the ambivalent effect of the tourism industry. Cuba had initially turned to tourism as a source of revenue during the “special period” of economic difficulties that followed the collapse of the USSR.

While tourism had undeniably restored and strengthened the Cuban economy, it had also led to increasing social differences, since Cubans who work in the tourism sector tend to make a much higher income than the average citizen. Though Cubans have free access to the beach, they are not permitted to enter resorts and hotels in tourist areas, which remain prohibitively expensive for many. Meanwhile, tourist areas require a large amount of water and electricity and can impact surrounding ecosystems.

Offering a Canadian analog to the Cuban situation, the Rev. Bill Mous—director of justice, community, and global ministries for the diocese of Niagara—noted that many people living in poverty in Canada would not be able to afford a stay at a domestic tourist destination such as Niagara Falls.

“I think the tourism talk left a big impression on me,” Canadian participant and first-year Trent University student Sierra Robertson-Roper said.

“I have family who have all come here and been tourists and stayed in Varadero, and I was a bit frustrated before I came because they kept telling me what I should expect, but they didn’t really have any kind of real experience of Cuba outside of a resort, which is Canadianized and Westernized … It was really enlightening for me to find out that Cubans weren’t allowed in resorts in their own country. It just really shows you the degree of separation.”

Climbing back aboard the bus, Justice Camp participants drove to Parroquia San Francisco de Asis (Parish of St. Francis of Assisi) in the nearby town of Cárdenas. There we enjoyed one of the best meals of many during the trip, with potatoes, salad, rice, tomatoes, what Bill and I agreed was some of the best fish we had ever eaten, and ice cream for dessert.

After filling our stomachs, church staff invited us to sit in the pews where we listened to Father Aurelio de la Paz Cot, translated by University of Havana professor Ida Ayala, describe different social ministries offered by the parish to the community. As rain poured down outside during a thunderstorm, we remained refreshingly cool despite the humid night air due to grates letting in breeze and electric fans installed on the church ceiling.

Father Aurelio highlighted 26 different ministries offered by the church to the local community in Cardenas, driven by five core purposes: worship, fellowship, discipleship, service, and evangelism.

Among its various ministries are:

- Open doors, inviting the community into church each day of the week;

- Purified water, which provides clean drinking water to the community;

- Assistance to the needy, operating both within and outside the congregation;

- Clothing for babies;

- Couples and marriage support, to help strengthen relationships;

- Consolation to families who have recently lost loved ones;

- Adult learning, offering lectures, dialogue and discussion; and

- Craftroom, encouraging creativity by producing arts and crafts.

Parroquia San Francisco de Asis was not the only church that social engagement participants visited during the three days of their immersion group, which also included trips to a farm and ecumenical hubs such as the Christian Centre for Reflection and Dialogue and the KAIROS Centre in Matanzas.

For Canadian participant Katelyn James—a member of St. John’s Church in Peterborough, Ont. who serves as program manager at the Warming Room, a winter response emergency shelter—being able to hear different perspectives was a major feature of the immersion experience.

“Definitely the highlight for me was spending time talking to the Cuban participants in our group about the realities in Cuba and some of the challenges and struggles that they face, and learning different stories that I really didn’t know anything about before coming here … It was humbling to have them share their stories with us.”

Read the conclusion of this report.

Interested in keeping up-to-date on news, opinion, events and resources from the Anglican Church of Canada? Sign up for our email alerts .